ADVOCACY & LEGISLATION

PCA Committees and Working Groups are led by our Members.

As the largest professional association representing Doctors of Chiropractic in Pennsylvania, public policy advocacy is a mission-critical function of the Pennsylvania Chiropractic Association.

As a PCA member or a Pennsylvania-licensed Doctor of Chiropractic, one of the most important things YOU can do to assist YOUR Chiropractic profession is to know your state legislators! Click here to find your local State Representative and State Senator. Interested in joining PCA’s mission to advance the profession? Email us to inquire about joining PCA’s Legislative Committee!

PCA LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

2021-2022

House Bill 225

Preauthorization Standards and Transparency in PA

Introduced by Representative Steven C. Mentzer

House Bill 173

Opening Up Health Care Networks in PA

“Any Willing Provider” (AWP) legislation introduced by Representative Anthony M. DeLuca

House Bill 325

Advisory Opinions from Licensing Boards

Introduced by Representative Keith J. Greiner

House Bill 171

An Act limiting restrictive covenants in health care practitioner employment agreements

Non-Compete Clauses in Health Care Employment introduced by Representative Anthony M. DeLuca

Political Action Committee

Political Action Committee Chair

Daniel Schatzberg, DC

Despite the Pennsylvania Chiropractic Association’s outstanding and numerous hard-fought and won legislative and regulatory victories, the most in this profession’s nearly 90-year organizational history in Pennsylvania, the battles facing our profession and patients are becoming more aggressive and more threatening to our profession. Denying patients’ access to needed care, increasingly without regard to any sense of ethics and decency, has become THE mantra of far too many health insurers in Pennsylvania today. These battles have affected EVERY Doctor of Chiropractic and Chiropractic patient in Pennsylvania today.

Accomplishments of PCA’s Political Actions

- We stopped repeated efforts by insurers to seriously compromise the very nature of our profession.

- We put an end to unwarranted and excessive multiple co-payments for patients IN ONE OFFICE VISIT.

- We put an end to unlimited retro-active reviews and take-backs from health insurers.

- We stopped efforts by BIG insurance and BIG business to drastically limit the rights of injured Pennsylvania workers and their treating DCs.

- We have continued to shine a light on the darkness of excessive overreach on restrictions to patients’ access to care by the wealthy health insurance industry and their lobbyists.

- We funded the appeal of the State Farm v. Cavoto legal case, specifically the right of DCs to delegate to unlicensed personnel.

- We advocated to the PA State Board of Chiropractic for specific regulatory language that addresses distance & classroom learning, delegation to unlicensed personnel, specialty advertising and scope of practice, including animal chiropractic.

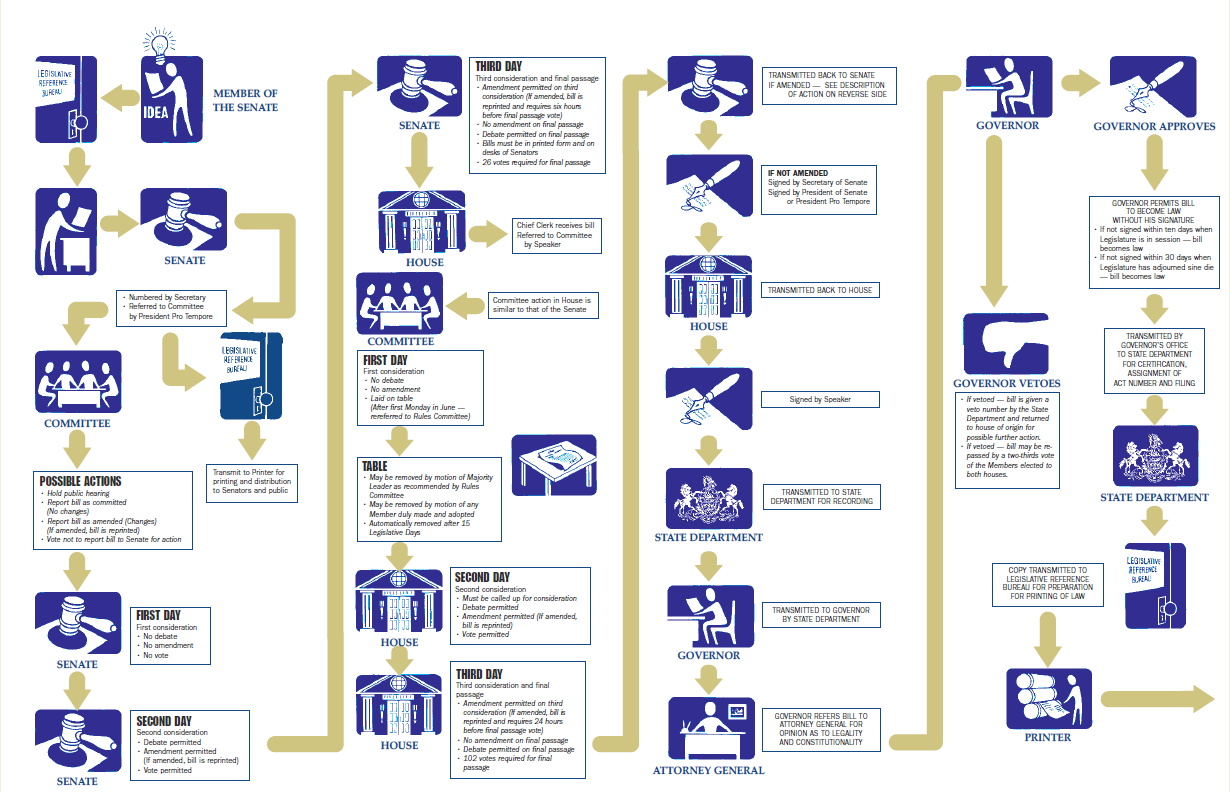

Legislative Process

The Lawmaking Power of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

Helpful Links & Information

Donate Now to PCA PAC

Anyone can make a donation to the PCA’s PAC Fund. You do not need to be a PCA member to donate.

Any individual may may make a donation to the PCA PAC Fund.

Donate Now to Legal Fund

Anyone can make a donation to the PCA’s Legal Fund. You do not need to be a PCA member to donate.

The Legislative Process

The Lawmaking power of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is vested by the Constitution in a General Assembly consisting of a Senate of fifty members, elected by the voters for a term of four years, and a House of Representatives of two hundred and three members, elected for a term of two years. Senators must be at least twenty-five years of age and Representatives at least twenty-one years of age. They shall have been citizens and inhabitants of the Commonwealth for four years, and inhabitants of their respective districts one year next before their election (unless absent on the public business of the United States or of this Commonwealth), and shall reside in their respective districts during their term of service.

The Legislature meets regularly every year for a two-year legislative session, as a continuing body, convening on the first Tuesday of January, and at other times when called into Special Session by the Governor on petition of a majority of the members elected to each house or whenever, in his opinion, the public interest requires. Since the General Assembly is a continuing body, sessions usually last throughout the year with occasional recesses.

The Lieutenant Governor, by virtue of the office, is the presiding officer of the Senate and, while serving in this capacity, is known as the President of the Senate. He/she has no vote except in case of a tie on certain matters. In his/her absence, the President Pro Tempore, a member of the Senate, presides.

At the beginning of the Regular Session when the House of Representatives meets for organization, it elects one of its members as Speaker to be their presiding officer. The Speaker, being a member, votes on all questions.

Proposed new laws or amendments to existing laws are introduced by individual members in the House or Senate in the form of bills as required by the Constitution.

The first step in lawmaking is for a member to submit ideas in writing to the Legislative Reference Bureau, which is the bill drafting agency of the General Assembly, outlining in substance what he/she desires in the proposed law. The bill is then drafted and typed in proper legal form. The member signs it, thereby assuming its sponsorship.

Senators introduce bills by filing them with the Secretary-Parliamentarian of the Senate who numbers the bills and delivers them to the President Pro Tempore for referral to a committee. Bills must be referred to a committee within 14 calendar days. After referral, the Secretary-Parliamentarian delivers the bills to the chairman of the committee.

A House member files bills with the Chief Clerk of the House. At the end of each day’s session of the House, the Chief Clerk delivers all bills which the House members have filed with him to the Speaker, who refers them to appropriate standing committees and reports his referral of each bill to the House at the next day’s session. Every bill, when introduced, is numbered and printed for the members of the House, the Senate and public distribution.

During the two-year session of the Legislature, be-tween 4,000 and 5,000 bills are introduced in both Houses, representing a wide range of subjects. Some are hundreds of pages in length. Many of these bills are highly controversial, requiring long debate and consideration of innumerable amendments. Obviously, it would be impossible for the Senate and House to get through the voluminous legislative business of enacting new laws; amending present ones; appropriating money; investigating governmental operations and all the other duties that devolve upon the General Assembly without the effective procedure of a committee system.

There are approximately twenty-two standing committees in the Senate and approximately twenty-seven with sub-committees in the House. These committees are the workshops of the General Assembly. It is their duty to study carefully the bills referred to them and to prepare bills which are to be reported with favorable recommendation to their respective houses. The popular opinion is that when the Legislature is not meeting, nothing is being done. The fact is that most of the work of the session is being carried forward by these standing committees when the General Assembly is not in session.

Once a bill is in committee, the committee has full power over it. Sometimes it is referred by the chairman to a sub-committee with instructions to study and make a report of its recommendations to the main committee.

After a committee has considered a bill, it may direct one of its members to report the bill to the Floor, either as committed (which means without change), as amended (with change), or, in rare instances with a negative recommendation. The committee may also decide not to report the bill at all.

The Senate or House, by a majority vote of the members elected, may discharge its committees from consideration of any bill.

Should a committee favorably report a bill in the Senate it is given a first consideration, unless there is an objection. (The Constitution of Pennsylvania requires that each bill shall be considered on three different days in both the Senate and House). No debate or amendments are permitted from the Floor at this stage.

After agreeing to the bill on first consideration, it is advanced to the calendar of bills for second consideration. This second consideration is the stage of passage when Senators may propose amendments from the Floor of the Senate, if they are germane to the subject of the bill. When a bill has been agreed to on second consideration, it is then placed on the next day’s calendar for third consideration, which means reprinting if it has been amended.

The next step is considering and agreeing to the bill a third time and advancing it to final passage, at which time its merits may be debated. On third consideration a bill may be amended. At the conclusion of the debate, the roll of Senators is called and, if a constitutional majority of twenty-six Senators votes in its favor, the bill passes the Senate. On a special class of appropriation bills, the Constitution requires a larger majority—two-thirds of the elected membership in each house.

After the bill has passed the Senate, it is transmitted to the House by the Message Clerk. The Chief Clerk of the House signs a receipt for the bill and it is then handed over to the Speaker, who refers it to one of the House Standing Committees.

If the bill is reported from committee, it follows some-what the same course of passage as in the Senate except in the area of first consideration. When the bill is reported from committee and given first consideration, it is not automatically moved on to a second consideration but is laid on the table. It may be removed from the table by a motion of the Majority Leader, or his designee, acting on a report of the Rules Committee. Such report must be in writing and a copy thereof distributed to each Member. When the bill is so removed from the table, it is placed on the second consideration calendar on the legislative day following such removal. This procedure does not prohibit any Member from asking a motion to remove the bill from the table. If the bill remains on the table for fifteen legislative days, it is automatically removed from the table and placed on the calendar for second consideration the next legislative day.

If the bill is reported from committee in the period between the first Monday in June and the first Monday in September, it is, after first consideration, re-referred to the Rules Committee. After the first Monday in September, all bills so rereferred are automatically reported from the Committee, laid on the table and then go through the procedure outlined above.

Second consideration, third consideration, and final passage procedure is the same as in the Senate with one hundred and two votes being the constitutional majority required for final passage in the House. If a bill is amended on third consideration, it is reprinted and requires 24 hours before final passage vote. The House may amend a Senate bill, in which case it is returned to the Senate for concurrence in the House amendments. The Senate may amend House bills in the same manner. Either house may defeat a bill of the other house, either in committee or on the Floor.

Should the Senate refuse to agree to the amendments made by the House, or vice versa, the bill usually goes to a Conference Committee made up of three members from each house, appointed by the Speaker of the House and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, whose duty it is to resolve, if possible, the differences existing between the two houses on the bill, and report to their respective houses. After a Conference Committee Report is presented, the Senate requires waiting six hours, and the House requires waiting 24 hours before voting, and a constitutional majority is required for the adoption of a Conference Committee Report.

When a bill has passed finally in both houses, it is signed by the President or President Pro Tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House in the presence of each house. It is then transmitted to the Governor for his consideration. If he approves, he signs the bill and it becomes a law. If he vetoes it, the bill is returned to the house of origin, together with the Governor’s reasons for the veto. The General Assembly has the power to pass a bill over the Governor’s veto by a constitutional vote of two-thirds of the Members elected to each house.

If the Governor does not act upon a bill within ten calendar days after it has been received by him, while the General Assembly is in session, it automatically becomes law. After final adjournment of the General Assembly, the Governor has thirty days to act upon the remaining bills passed by both houses. Bills on which he takes no action automatically become law. It is rare indeed for a bill to become law by reason of the Governor taking no action.

The official certified copy of each bill approved by the Governor is placed in the custody of the Secretary of the Commonwealth, given an act number and filed in the State Department. It then loses its identity as a bill and becomes an “Act of the General Assembly.” The Legislative Reference Bureau, the agency in which the bill originated, prepares the act for printing. The Director of the Bureau, in punctuating and editing the act may, with the approval of the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the Office of Attorney General, make any corrections which will not in any manner affect or change the meaning, intent or substance of the act. Examples of such corrections are misspelled words, typographical errors, plural or singular number, past, present or future tense appears where another should be used, a word clearly should have been omitted, etc. After all this is done, the Bureau publishes the acts in book form, known as the Pamphlet Laws, for distribution to the courts, attorneys, libraries and citizens of our Commonwealth who may request them. There is also an individual copy of the act printed for distribution and they are called “advanced copies of enacted statutes.” This saves sending a copy of the bound P.L.s when just one act is desired – this then is the law.

The accompanying diagram shows in graphic form the stages through which a bill passes in becoming a law.